Former President Joe Biden signed the Good Samaritan Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act on December 19 with minimal media coverage outside of a few Western states. The law, which had been in the works for over two decades, was bipartisan. Some have praised it as the most significant environmental law to be passed in decades.

Biden signs legislation to clean up the western United States’ abandoned mines.

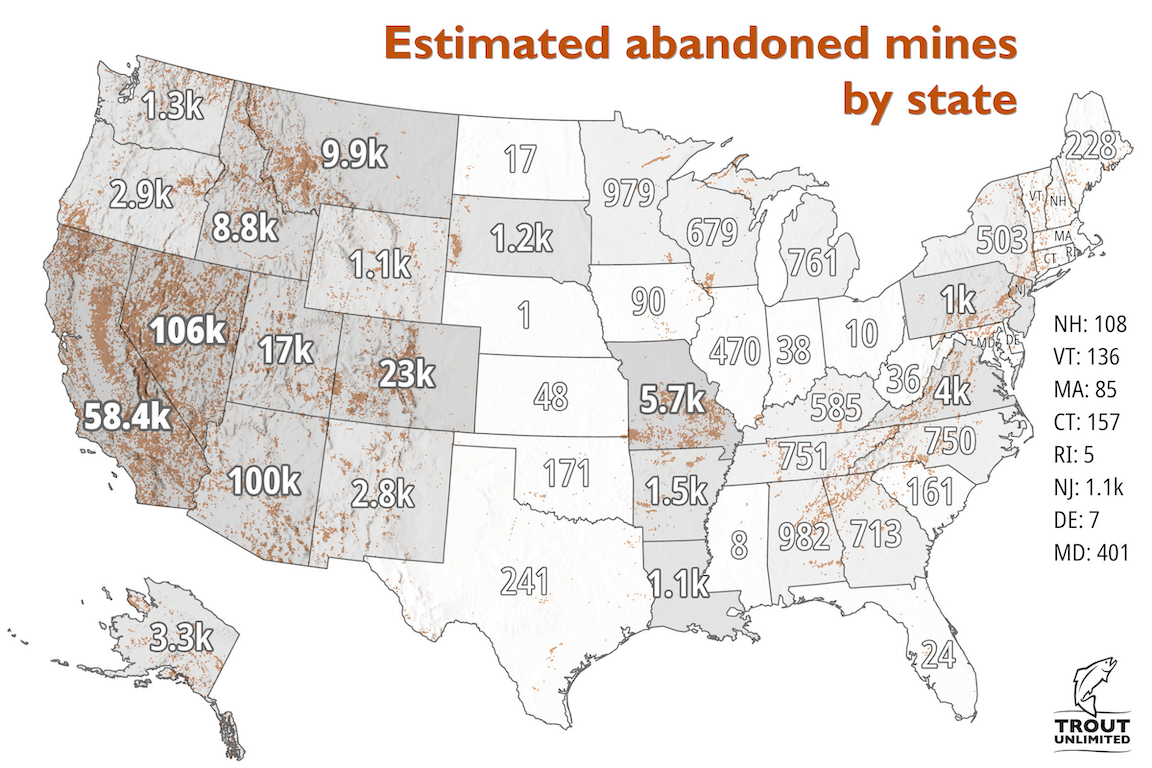

The problem might not be well known in New Hampshire. We don’t often consider our state to have ancient, abandoned mines that are contaminating our water supplies due to past mistreatment or negligence. The Western United States is home to the majority of the hundreds of thousands of hardrock miners that discharge lead, arsenic, and other heavy metals into our waterways. For instance, there are an estimated 8,800 of these mines in Idaho and 106,000 in Nevada. There are still about 100 in New Hampshire.

There are a few abandoned mines in New Hampshire that are causing serious contamination, but the majority are not. The federal government paid more than $3 million to clean up the Ore Hill Mine in Warren, which is now on White Mountain National Forest property, since it was poisoning surface water. They still pay around $40,000 annually to preserve and monitor the facility. Ponds downstream still contain acidic water from two additional closed mines: the Madison Lead Mine and the Mascot Mine near Gorham. Mascot Pond’s sediments contain 200 times the natural amount of lead. Lead pond sediments were more than 75 times normal, zinc levels were 100 times normal, and mercury levels were almost twice as high in the pond beneath the Madison Mine as in an adjacent unimpacted pond.

The majority of these mines continue to contaminate our waterways across the nation for complex reasons. The majority of the mines were established many decades ago before their operations were subject to environmental regulations. They were abandoned once they ceased to produce material in economically viable quantities. In more recent times, when the owners filed for bankruptcy, the public was left to bear the burden. In any case, the government and taxpayers were held accountable for these environmental catastrophes. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to find public funds to address this issue.

Cleaning up the worst of the pollution from some of these mines has been a long-standing goal for several states, towns, and conservation organizations. However, two rules that basically state that “if you touch it, you own it” stopped them. Unless they could completely clean the mine to meet the requirements of the Superfund Act or the Clean Water Act, whomever took up cleanup would be held fully liable for the mine’s liabilities. Technically and financially, that objective is frequently unachievable.

However, if the project can eliminate the majority of the pollutants, shouldn’t it be feasible to undertake the effort? That hasn’t been the case up until now.

Because of this, these organizations, known as Good Samaritans, have been reluctant to take any action for fear of being held legally accountable for all the pollution as though they were the mine’s owners.

Co-sponsor U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich of New Mexico argued for the bill, saying: Good Samaritans have been working to clean up abandoned mines for over 25 years, but they have encountered many obstacles and liability regulations that make them liable for all pre-existing pollution from a mine even though they had no prior connection to the mines.

This type of pollution deteriorates streams over 100,000 miles in the United States. In the Western United States, previous mining activity has contaminated 40% of the headwater streams that feed rivers that supply drinking and agricultural water.

The anticipated cost of cleaning up this disaster would exceed $50 billion. Over the last ten years, federal funding of $2.9 billion has hardly begun to address the issue.

Up to 15 low-risk pilot projects by third-party applicants are now possible under the new rule. One of those applications will probably be Trout Unlimited, a nationwide conservation group committed to preserving and improving clean water for the benefit of our communities and fisheries.

For decades, Trout Unlimited has been actively addressing issues related to abandoned mines, gaining a wealth of knowledge and knowing how to secure funding for this work. But up until now, it was unable to complete the task due to the enormous financial risk posed by the idea that “if you touch it, you own it.”

Lastly, the necessary work will be permitted to be done by good people and organizations who wish to address a problem that they did not cause.

For the communities that rely on clean water and a healthy environment, this is a huge victory. In New England, where there are just 700 abandoned mines, it might not have made much of a splash, but it certainly did for the rest of the nation.

Trout Unlimited’s national board of trustees includes Paul Doscher, a retired environmental scientist from Weare, New Hampshire.

Like the Idaho Capital Sun, the New Hampshire Bulletin is a member of States Newsroom, a 501c(3) public charity news network backed by grants and a coalition of donors. The editorial independence of the New Hampshire Bulletin is maintained. For inquiries, send an email to [email protected], the editor Dana Wormald.